The Rediff Special/ Rong Ying

Forty years ago, a border conflict broke out between China and India, two neighbours that had maintained traditional friendship for thousands of years and had fought no wars. Since then, the "brothers" have been bogged down in long-term confrontation and mistrust and the boundary question remains unresolved.

Forty years ago, a border conflict broke out between China and India, two neighbours that had maintained traditional friendship for thousands of years and had fought no wars. Since then, the "brothers" have been bogged down in long-term confrontation and mistrust and the boundary question remains unresolved.

I have read many recent articles in the Indian media, both print and electronic, on the border conflict. To be frank, some of the viewpoints were either misleading or a distortion of the facts, which will not help the friendly relations between China and India.

Dispelling the mist over the 1962 border conflict and clarifying the historic facts will not only help get rid of this hang-up between the two peoples, but also create favourable conditions for settlement of the boundary question and promote steady progress of China-India friendship and cooperation.

The boundary between China and India has never been formally delimited. But the two peoples had been living together in peace and harmony, and no dispute had even arisen before the arrival of the British colonialists. This was because a traditional customary boundary line had long taken shape on the basis of the extent of each side's administrative jurisdiction in the long course of peaceful existence. This line was respected by both the Indians and the Chinese.

The eastern sector of this traditional customary boundary runs along the southern foot of the Himalayas, the middle sector along the Himalayas, and the western sector along the Karakoram range. This traditional boundary was not only respected by China and India over a long period of time, but also reflected in early official British maps.

Before 1685, the delineation of the western sector of the Sino-Indian boundary in official British maps coincided roughly with the traditional line, and before 1936 so did the eastern sector. But from the second half of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th, British imperialism was actively engaged in conspiratorial activities of aggression against China's Tibet and Sinkiang provinces.

Various attempts were made to obliterate the traditional boundary line, carve up China's territory, and expand the territory of British India. At the Simla Conference in 1914, the British representative drew the notorious "McMahon Line" through a secret exchange of letters with the representative of the Tibetan local authorities, attempting thereby to annex 90,000 square kilometres of Chinese territory.

Various attempts were made to obliterate the traditional boundary line, carve up China's territory, and expand the territory of British India. At the Simla Conference in 1914, the British representative drew the notorious "McMahon Line" through a secret exchange of letters with the representative of the Tibetan local authorities, attempting thereby to annex 90,000 square kilometres of Chinese territory.

In the western sector, British imperialism laid covetous eyes on Aksai Chin in the 1860s by sending military intelligence agents to infiltrate into the area for unlawful surveys and working out an assortment of boundary lines.

The British attempt to impose the McMahon Line on the Chinese and alter to its own wishes the traditional border in the western sector was promptly rebuffed by the then government of China and successive Chinese governments. Therefore, from 1865 to 1953 British and Indian maps either did not show any alignment of the boundary in the western sector, or showed it in an indistinct fashion and marked it as undefined. And it was only from 1936 onwards that the illegal McMahon Line in the eastern sector appeared on British and Indian maps, but up to 1953 it too was designated as undemarcated.

It was not until the last phase of World War II that British imperialism started to intrude into and seize a small part of the area lying south of the illegal McMahon Line and north of the Sino-Indian traditional border.

In 1947 and 1949, respectively, India and China attained independence. Thanks to their mutual efforts, they established diplomatic relations quite early, jointly initiated the famous Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence, and signed the Agreement on Trade and Intercourse Between the Tibet Region of China and India. This helped bolster friendly relations between the two countries.

The Chinese government has held that in dealing with the boundary question, neither China nor India should shoulder the blame for the legacy created by imperialists. Since both had won their independence, each side should overcome the interference of history and seek a settlement of all unresolved issues, including the boundary question, in a spirit of mutual understanding and accommodation.

But after the founding of New China and particularly after the peaceful liberation of Tibet, the Indian government pressed forward in an all-out advance on the illegal McMahon Line in the eastern sector and completely occupied Chinese territory, including Tawang, south of that line and north of the traditional boundary.

The Chinese government did not accept the Indian encroachment, but took the position that an amicable settlement should be sought through negotiations, and that, pending a settlement, the status quo of the boundary should be maintained. China still does not recognise the so-called McMahon Line, yet in the interest of settling the Sino-Indian boundary question through negotiations, it has refrained from crossing it.

From 1950 to 1958, tranquillity prevailed along the Sino-Indian border because China adhered to the policy of seeking an amicable settlement of the boundary question. But when a rebellion of serf-owners broke out in Tibet, the Indian government not only aided and abetted it and connived at their anti-Chinese political activities in India, but also formally presented to the Chinese government a claim to large tracts of Chinese territory.

It not only asked Beijing to recognise as legal Indian occupation of Chinese territory in the eastern sector, but also to recognise as part of India the Aksai Chin area in the western sector, which India had never occupied.

The gravity of the situation lay not only in India's extensive claims to Chinese territory, but also in its subsequent use of force to unilaterally change the state of the boundary.

In August 1959, Indian armed forces crossed the McMahon Line in the eastern sector and invaded and occupied Longju and other areas north of the line; and in October 1959 Indian armed forces crossed the traditional boundary in the western sector as well. In the course of the invasion, Indian armed forces provoked sanguinary border clashes at Longju and Kongka Pass.

The Chinese government held that to avert new conflicts and prevent a deterioration of the situation, ways must be found to effect a disengagement of the armed forces of the two sides, and at the same time negotiations must be started quickly to seek a peaceful settlement of the boundary question.

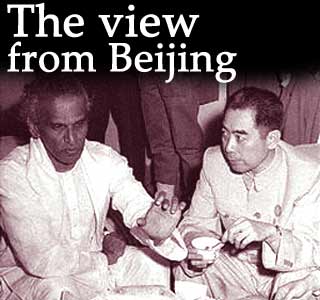

On November 7, 1959, China's Premier Zhou Enlai wrote a letter to Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru proposing that both sides withdraw their armed forces 20 kilometres from the Line of Actual Control along the entire Sino-Indian border and halt patrols.

The LAC referred to coincided with the traditional boundary in the western and middle sectors except for the parts of Chinese territory that India had invaded and occupied; in the eastern sector, it coincided with the illegal McMahon Line except for Khinzemane, which was then still under Indian occupation. Premier Zhou also proposed that the prime ministers of the two countries discuss the boundary question.

But the Indian government rejected these proposals. On November 16, 1959, it put forward a counter-proposal, suggesting that all Chinese personnel in the Aksai Chin area of China's Sinkiang withdraw to the east of the line that India claimed to be the international boundary, and all Indian personnel in this area withdraw to the west of the one that China claimed to be the international boundary.

But the Indian government rejected these proposals. On November 16, 1959, it put forward a counter-proposal, suggesting that all Chinese personnel in the Aksai Chin area of China's Sinkiang withdraw to the east of the line that India claimed to be the international boundary, and all Indian personnel in this area withdraw to the west of the one that China claimed to be the international boundary.

Since Indian personnel had never actually come into this area, the Indian proposal was tantamount to demanding the unilateral withdrawal of Chinese personnel from vast tracts of their own territory. This was obviously rejected by the Chinese government.

Despite this, the Chinese government maintained that it was of paramount urgency to avert conflict along the border. Hence it unilaterally discontinued patrols on its side of the boundary in the hope that a disengagement of the armed forces of the two sides could be conducive to avoiding border clashes and maintaining tranquillity.

To prevent a deterioration of the situation, Premier Zhou and Vice-Premier and Foreign Minister Marshal Chen Yi visited New Delhi in April 1960 and held extensive talks with Prime Minister Nehru and other Indian leaders. At the conclusion of the talks, Premier Zhou summed up the following six points as points of common ground or of close proximity emerging from the talks:

- There exist disputes with regard to the boundary between the two sides.

- There exist between the two countries a line of actual control up to which each side exercises administrative jurisdiction.

- In determining the boundary between the two countries, certain geographical principles, such as watersheds, river valleys, and mountain passes, should be equally applicable to all sectors of the boundary.

- A settlement of the boundary question between the two countries should take into account the national feelings of the two peoples towards the Himalayas and the Karakoram mountains.

- Pending a settlement of the boundary question through discussions, both sides should keep to the line of actual control and not put forward territorial claims as pre-conditions, but individual adjustments may be made.

- To ensure tranquillity on the border so as to facilitate the discussion, both sides should continue to refrain from patrolling along all sectors of the boundary.

The Chinese government expressed the hope that these points of common ground would be affirmed so as to facilitate further discussion by the two governments. But the Indian side refused.

This meant that New Delhi was unwilling to recognise the existence of a line of actual control between the two countries, was unwilling to agree to observe this line pending a settlement of the boundary question through negotiations and refrain from putting forward territorial claims as pre-conditions to negotiations, was unwilling to disengage the armed forces of the two sides to forestall border clashes, and was even unwilling to recognise the objective fact that there existed disputes between the two sides.

Hence, three further meetings between officials of the two countries in Beijing, New Delhi, and Yangon from June to December 1960 failed to yield results.

In the following years of 1961 and 1962, the sincerity for conciliation demonstrated by the Chinese government during talks between the prime ministers was taken by the Indian side to be an indication that China was weak and could be bullied, and China's unilateral halting of border patrols was taken as an opportunity to be seized.

Indian troops adopted a "forward policy" by making repeated inroads into Chinese territory. They soon established a total of 43 outposts encroaching on Chinese territory in the western sector prior to the general outbreak of clashes. Some were set up only a few metres from Chinese posts, other even behind Chinese posts, cutting off their access to the rear.

Indian troops adopted a "forward policy" by making repeated inroads into Chinese territory. They soon established a total of 43 outposts encroaching on Chinese territory in the western sector prior to the general outbreak of clashes. Some were set up only a few metres from Chinese posts, other even behind Chinese posts, cutting off their access to the rear.

In the eastern sector, Indian troops crossed the illegal McMahon Line, intruded into the Che Dong area north of the line, and launched a series of armed attacks on Chinese frontier guards. Thus, before the full-scale border conflict broke out, the Indian side had already created an explosive situation in both the eastern and western sectors.

Despite that, Beijing maintained maximum self-restraint. Chinese frontier guards were ordered not to fire the first shot in any circumstance, nor to return fire except as a last resort. Beijing also sent protests and warnings to the Indian government, declaring that it would never accept the Indian encroachments and firmly demanding that India evacuate Chinese territory. It also reiterated its efforts to seek an improvement in Sino-Indian relations and a peaceful settlement of the boundary issue through negotiations.

But New Delhi not only repeatedly rejected the fair proposal of the Chinese, but added new and more pre-conditions, finally blocking the door to negotiations. On October 12, 1962, Prime Minister Nehru declared that he had issued orders to "free" what he termed invaded areas, in reality Chinese territory, of Chinese troops.

On October 14, then Indian defence minister Krishna Menon called for fighting China to the last man and the last gun. Afterwards, Indian troops accelerated combat preparations, and launched massive attacks all along the line. It was only when they were pressed beyond the limits of forbearance and left with no room for retreat that the Chinese frontier guards struck back in resolute self-defence.

On October 24, four days after the border conflict broke out, the Chinese government issued a statement putting forward three proposals to stop the border conflict, reopen peaceful negotiations, and settle the boundary question; but they were again rejected by India. What needs to be pointed out is that one of the three proposals was that the two sides respect the line of actual control along the entire border and the armed forces of each withdraw 20km from that line and disengage.

The LAC referred to in the three proposals did not mean the line of actual contact between the armed forces of the two sides in the border clashes, but the line of actual control that existed along the entire border when Premier Zhou mentioned it to Prime Minister Nehru in his letter of November 7, 1959. The essence of this proposal was to restore the state of the Sino-Indian boundary to the 1959 position, that is, before complications arose.

The LAC referred to in the three proposals did not mean the line of actual contact between the armed forces of the two sides in the border clashes, but the line of actual control that existed along the entire border when Premier Zhou mentioned it to Prime Minister Nehru in his letter of November 7, 1959. The essence of this proposal was to restore the state of the Sino-Indian boundary to the 1959 position, that is, before complications arose.

But Delhi insisted that no negotiations were possible unless the state of the entire boundary as it prevailed before September 8, 1962, was restored. This implied that in the eastern sector, Indian troops would reoccupy Chinese territory north of the illegal McMahon Line; in the western sector, they would invade and reoccupy military strong points they had set up on Chinese territory after 1959. This was not fair, and was rejected by the Chinese side.

On November 21, 1962, the Chinese government issued a statement that from October 22, 1962, the Chinese frontier guards would observe a ceasefire along the entire Sino-Indian border, and from December 1, 1962, the Chinese frontier guards would withdraw 20km from the line of actual control existing along the entire border on November 7, 1959.

In the eastern sector, the counter-attack of self-defence was launched in the area of Chinese territory north of the traditional boundary, but the Chinese frontier guards were ready to withdraw from their positions to the line of actual control, that is, 20km north of the McMahon Line. In the middle and western sectors, the Chinese side would withdraw 20km from the line of actual control.

What must be pointed out is that the positions of the Chinese frontier guards after their stated withdrawal would be much farther away from their positions before September 8, 1962. These measures fully demonstrated the sincerity of the Chinese side to stop border conflicts and seek a peaceful settlement of the dispute.

The Chinese side also expressed its willingness to hold a meeting between the prime ministers of the two countries after related measures were implemented so as to seek a friendly settlement of the boundary question. On December 10, 1962, the Indian government, persuaded by Egypt and other five non-aligned nations, finally accepted the Chinese proposals.

This historic truth of the border conflict clearly shows that it was solely created by the then Indian government, which insisted on having its own way by stubbornly clinging to its wrong position, refusing to accept the peace proposals of the Chinese, and embarking on the road of military adventurism. It was not China's "invasion" or "betrayal" of India, nor an "India war" waged by Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, who had the so-called agenda "to split India and compete for the leadership with Jawaharlal Nehru of developing countries".

Forty years have passed, and the domestic and international environments of China and India have both undergone dramatic changes. Through peaceful negotiations, China has settled almost all the boundary questions with all its neighbours left over from history.

As for the Sino-Indian boundary question, the two governments, after many rounds of talks since 1981, have reached a consensus of "mutual understanding and mutual accommodation" and "mutual adjustment" to settle the issue. In 1993 and 1996, China and India signed two important agreements on the boundary question -- one on the maintenance of peace and tranquillity along the LAC and another on confidence-building measures along the LAC. The former was exactly what Premier Zhou had proposed in his letter to Prime Minister Nehru on November 7, 1959.

Since the establishment of the Joint Working Group, a lot of work has been done, and many rounds of negotiations have been held. The process of verification of the LAC along the boundary is proceeding, and some progress has been achieved. The two nations have also made steady and positive progress in developing relations in the fields of economy and trade, science and technology, and culture. Frequent high-level visits by both sides have deepened mutual understanding between the peoples.

Since the establishment of the Joint Working Group, a lot of work has been done, and many rounds of negotiations have been held. The process of verification of the LAC along the boundary is proceeding, and some progress has been achieved. The two nations have also made steady and positive progress in developing relations in the fields of economy and trade, science and technology, and culture. Frequent high-level visits by both sides have deepened mutual understanding between the peoples.

Nevertheless, what needs to be pointed out is that verification of the Line of Actual Control is different from delimitation and demarcation of the border. No attempt should be made to impose the illegal McMahon Line by taking advantage of the process of verification of the LAC. The Chinese government did not recognise the line yesterday; it does not recognise the line today, nor will it recognise the line tomorrow.

As a scholar, I sincerely hope that China and India settle their boundary question at the earliest, eliminating a major obstacle to the smooth development of friendly and cooperative relationship between them. Pending this, the two sides should continue to maintain peace and tranquillity in the border areas, create conditions conducive to settle the boundary question, and vigorously develop friendship and cooperation in the political, economic, scientific and cultural fields.

In the new century, China and India, the two largest developing countries, should join hands to make more contributions to peace and stability in the region and the world at large.

Rong Ying is deputy director for South Asian, Middle Eastern and African studies, China Institute of International Studies, Beijing. He can be reached at rongying@ciis.org.cn