The Rediff Special/Maj Gen (retd) K K Tewari, PVSM, AVSM

As a result of the Chinese threat on our northern borders, some time in 1959 the headquarters of the Eastern Command at Lucknow was given the operational responsibility for the defence of the borders in Sikkim and NEFA.

As a result of the Chinese threat on our northern borders, some time in 1959 the headquarters of the Eastern Command at Lucknow was given the operational responsibility for the defence of the borders in Sikkim and NEFA.

I was at that time on the staff at HQ Eastern Command. The 4th (Red Eagle) Infantry Division was located at Ambala. Soon after it was ordered to move to Tezpur in Assam towards the end of 1959, I was posted as its Commander, Signals.

This division, trained and equipped for fighting in the plains, had suddenly been deployed to guard the borders in this high mountainous region. While a normal division is expected to defend a 30-40km front in the plains, we were assigned a front spanning more than 1800km of mountainous terrain.

Worse was to come. Even before the division could take over its operational responsibilities to defend the border with Tibet, orders for the execution of Operation Amar 2, for construction of accommodation for ourselves, were received from Army HQ.

This was the brainchild of Lt Gen B M Kaul, then Quartermaster General at Army HQ. We were supposed to build temporary basha accommodation. Besides the fact that my regiment had to provide communications for the division in an entirely new and undeveloped area, we had now to become engineers and labourers!

My first four months in command were a real nightmare. We would certainly have preferred to rough it out in tents and spend the time developing a reasonable communications set-up, getting our equipment properly checked and maintained, and getting the men used to working with the available equipment, which was antiquated and unsuitable for mountainous terrain and the excessive ranges.

Even at that time, there were hardly any roads in any of the five frontier divisions (FD) of Arunachal Pradesh. The road into Kameng FD, the most vulnerable, finished at the foothills just beyond Misamari.

We were faced with shortages of every kind. It was during these early days in NEFA that one of the commanding officers of an infantry battalion sent an official reply written on a chapati. When asked for an explanation, he gave a classic reply:

"Regret unorthodox stationary but atta [wheat flour] is the only commodity available for fighting, for feeding, and for futile correspondence."

Sometime in 1962, orders came from Army HQ for Operation Onkar (the famous "Forward Policy"), which directed all Assam Rifles posts to move forward, right up to the border.

Of course, we in the army were to back them. The idea was to establish the right of possession on our territory and to deter the Chinese from moving forward and occupying the territories claimed by them. But this order was certainly not backed up with resources.

At that time, our division had done almost three years non-family station service, and some of the units were already on their way out on turnover. Suddenly all moves out of the area were cancelled and orders reversed.

At that time, our division had done almost three years non-family station service, and some of the units were already on their way out on turnover. Suddenly all moves out of the area were cancelled and orders reversed.

Brig John Dalvi, commander of the 7th Infantry Brigade in Tawang, was ordered to move his HQ on a man/mule pack basis to Namka Chu River area. An ad-hoc brigade HQ was created for the Tawang sector overnight with hardly any signal resources.

At that time, I was the only field officer of lieutenant colonel or higher rank who had the longest tenure not only at the divisional HQ but among all the divisional troops. I should have been posted out after a two-year tenure in a non-family station.

But I had also a sort of premonition, and I recorded it in my diary, that a severe test was in the offing for me to assess my faith in the Divine. I certainly had no idea that I would be taken a prisoner of war.

On September 8, 1962, the Dhola post manned by the Assam Rifles on the McMahon Line was encircled by the Chinese. After this incident, a new corps HQ was created to take charge of operations in NEFA. Lt Gen B M Kaul was appointed corps commander. He arrived from Army HQ in a special aircraft at Tezpur in the late afternoon of October 4. He went straight into a conference and at about 10pm, announced in his typical flamboyant style that he had taken over command of all troops in NEFA. It was all so dramatic!

Here was a new situation. Normally, in those days, a corps HQ would be served by a corps signal regiment and another communication zone signal regiment to back it. But these had yet to be raised and my regiment had to take on the load of not only our own division, but the new corps HQ also.

To add to these difficulties, Lt Gen Kaul had his own way of sending messages.

Normally, a signal message is supposed to be written in an abbreviated telegraphic language. But all messages from the new corps commander ran into a couple of typed sheets in prose and were all marked Top Secret and Flash.

They were not addressed to the next higher HQ, but directly to Army HQ. You should understand that normally Signals are required to stop all other traffic to clear FLASH messages and these messages also have to be enciphered first.

In September 1962, the higher authorities had obviously assumed that it would be easy to beat the Chinese. Otherwise, one cannot imagine how such an order to engage the enemy could have been issued by Delhi to the ill-equipped, ill-clothed, ill-prepared, fatigued, disillusioned troops.

When Dalvi's brigade arrived near the Namka Chu River after forced marches, he was ordered to throw the Chinese out of the Thagla ridge.

Arriving at the destination after an exhausting journey, my brigade signal officer discovered that the generating engine to charge the wireless batteries was missing. A porter had dropped it in a deep khud on the way, and it could not be retrieved.

I think it was dropped deliberately, because I knew some of these civilian porters were in the pay of the Chinese.

I think it was dropped deliberately, because I knew some of these civilian porters were in the pay of the Chinese.

But I was in for a bigger shock when it was discovered that almost all the secondary batteries had arrived without any acid. I presume that what had happened was that the porters must have found it lighter without liquid and they probably decided to lighten their loads by emptying out the acid from all the batteries.

How to establish communications when the batteries were dead and could not be recharged without an engine? Despite our good relations with them, the air force helicopter boys refused to carry acid. There was no question, of course, of dropping sulphuric acid by air. What was I to do?

Finally, we filled up a jar of acid and marked it prominently: `Rum for Troops'. On October 18, I flew from Tezpur to Zimithang where I met the GOC, Maj Gen Niranjan Prasad. Later, I went to Tsang Dhar near the Namka Chu River in a two-seater Bell helicopter with just the pilot and with the 'Rum' jar strapped onto my lap.

I landed there in the late afternoon and marched down to Brig Dalvi's brigade HQ. As I arrived, I could quite clearly see the massing of the Chinese troops on the forward slopes of Thagla ridge.

But when I discovered that every unit on the front had numerous Signals problems, I decided to extend my stay by a day. Not knowing that the fates had other things planned for me.

On the 19th, Brig Dalvi talked on the telephone with the GOC at Zimithang. He pleaded with his boss to let him move out of the `death trap', up to a tactically sound defensive position.

Brig Dalvi was told not to flap, but to obey orders and stay put. He was extremely upset and passed the telephone to me saying, "You won't believe me, Sir, but talk to your 'bloody' commander Signals and he will tell you what all he can see with his naked eyes in front."

I spoke to the GOC equally strongly saying that one could see the Chinese moving down the Thagla ridge like ants with at least half a dozen mortars, which were not even camouflaged. I added that the Chinese could not have been there for a picnic.

But I was also told to concentrate on my work and not to worry.

I stayed on with the Gorkhas during the night of 19th October. Early on the 20th morning, I was woken up from deep sleep by the noise of intense bombardment. There was utter confusion in the pre-dawn darkness, with people shouting and yelling and running around in the midst of these exploding shells.

I came out of the bunker and somehow found my way to the Signals bunker with two of my signalmen. But when I looked out of the bunker, I was mystified to see no visible movement outside. There was no one in sight. But I could hear short bursts of gunfire.

When I peeped out of the bunker again, I saw a line of khaki-clad soldiers with a prominent red star on their uniforms advancing towards our bunker. I had never seen a Chinese soldier till then at such close range.

I used to carry a 9mm Browning automatic pistol in those days with one loaded clip. The thought immediately was that one's body should not be found with an unfired pistol; it must be used, however hopeless our situation. So, when a couple of Chinese soldiers approached our bunker, I let go the full clip at them.

I used to carry a 9mm Browning automatic pistol in those days with one loaded clip. The thought immediately was that one's body should not be found with an unfired pistol; it must be used, however hopeless our situation. So, when a couple of Chinese soldiers approached our bunker, I let go the full clip at them.

This provoked a lot of yelling and firing and a number of the soldiers converged onto our bunker. My two assistants were killed, but I was still alive, though a PoW now.

The same day we were marched along a narrow track across the Namka Chu River and later we went up to the Thagla Pass (about 15,000 feet). On our way, we passed huge stocks of unfired mortar shells by the sides of all the mortar positions, while on the northern side, we saw Chinese parties bringing up 120mm mortars on a man pack basis.

After three days' walk, we reached a place called Marmang in Tibet. From there we were taken in covered vehicles at night. During the journey, the Chinese tried to demoralize us; they would make fun of our army: "You do not even have cutting tools for felling trees. You use shovels to cut down trees."

It was true; they had seen our troops preparing their defensive positions near the Namka Chu River. There were other remarks, such as, "You people have strange tactics. You sit right at the bottom of the valley to defend your territory instead of sitting on high ground."

We arrived at the PoW camp located at Chen Ye [Chongye in central Tibet] on October 26 and were accommodated in lama houses, which were all deserted, although we could see some activity in the monastery above these houses on the side of a hill.

We were to spend over five months in this camp, located southwest of Tsetang, off the main highway to Lhasa. The prisoners were segregated into four companies: No 1 company was all officers, JCOs and NCOs. Majors and lieutenant colonels were also separated from the JCOs and men. No 2 and 3 companies were jawans of various units. No 4 company consisted only of Gorkhas and was given special privileges, for obvious political reasons. Each company had its own cookhouse where the Indian soldiers selected by the Chinese were made to cook.

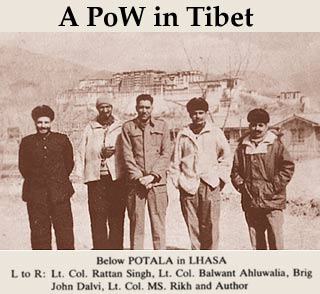

In our house, we were four lt colonels (M S Rikh of the Rajputs, Balwant Singh Ahluwalia of the Gorkhas, Rattan Singh of 5 Assam Rifles and myself), while John Dalvi was kept in confinement in Tsetang, a few kilometres away from Chongye.

When we made representations to the Chinese that under the Geneva Convention on PoWs, officers had the right to be with their men, we were told quite bluntly that all these were nothing but imperialist conventions.

I shivered through the first couple of nights, but then had a brain wave. I had noticed a pile of husk outside. We asked the Chinese if we could use it. Luckily, they accepted, and we could use the stuff as a mattress as well as a quilt to keep warm.

For almost a month after our arrival, we were not let out of the room. Each of these lama houses had its own latrine in one corner with an open but very effective system of soil disposal. Unfortunately, by the time we arrived, the 'disposal squad' of pigs had itself been disposed of by the Chinese.

There was an English-speaking Chinese officer, Lt Tong, who was with us almost throughout our stay in the PoW camp. He would come daily and talk to us individually or together.

The theme of his talk with the PoWs was monotonously the same: the Chinese wanted to be friends and it was only the reactionary government of Nehru, who was a lackey of American imperialism, which wanted to break this friendship. "Then why did you attack us on October 20?" was our reaction. They would try to explain that India attacked first and the Chinese attacked only in self-defence.

The theme of his talk with the PoWs was monotonously the same: the Chinese wanted to be friends and it was only the reactionary government of Nehru, who was a lackey of American imperialism, which wanted to break this friendship. "Then why did you attack us on October 20?" was our reaction. They would try to explain that India attacked first and the Chinese attacked only in self-defence.

On December 5, we were given for the first time some books and magazines to read. This consisted of Mao's Red Book, some literature on the India-China boundary question, and a few Red Army journals. But whatever they were, they were most welcome for me at least. There was something to do at last to occupy the mind. I took notes from the Red Book.

It is a pity that our government had not taken note of some of the Mao's thoughts. I noted down a few at that time: "Fight no battle unprepared, fight no battle you are not sure of winning", or "The enemy advances, we retreat; the enemy halts, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue."

Towards the end of December 1962, the Indian Red Cross sent us some parcels, each with two packets in it. One packet had warm clothes, a German battle dress, a pair of long johns, warm vest, muffler, cap, jersey, warm shirt, boots and a towel. The second packet contained foodstuff, including a bar of Sathe chocolate, tins of milk, jam, butter, fish, sugar, atta (wheat flour), dal (pulses), dried peas, salt, tea, biscuits, condiments, cigarettes, and vitamin pills. It certainly was a very well thought-out list of items.

Perhaps to demoralize us, the Chinese would often play Indian music on the public address system in the camp. One of the songs which was played repeatedly was Lata Mangeshkar's "Aa ja re main to kab se khari is paar... (come, I have been waiting for so long...)" This would make us feel homesick.

With my habit of writing a diary, I kept notes as a PoW also. The only available paper to write on in the first week or so were some sheets of toilet paper in my para jacket pocket. The question was how to keep these papers from being discovered by the Chinese. What I had done was to open the stitching on the `belt' part of the trousers and slide the folded papers inside. This was how my diary notes on toilet paper could be brought out to India.

One day, towards the end of our stay, at our request we were taken to see the palace and the monastery. It was a shock to see the palace with all the beautiful Buddha statues of all sizes and fabulous painted scrolls [thankas] lying broken, defiled, and torn and trampled on the ground.

On December 25, we, the seven field officers, were taken in one of the captured Indian Nissan trucks to spend the Christmas morning with Brig John Dalvi at Tsetang. He was kept all alone and was comfortably accommodated. We had breakfast and lunch with him and were shown a movie. But the solitary confinement had left its scars on him.

The first letters we received from home came only in the third week of February 1963. Some of us also received parcels of sweets.

On March 26, we were informed that we would soon be released and taken for a conducted tour of mainland China. Suddenly we became VIPs, though still held prisoner. We were given various comforts and new clothes and shoes.

Before leaving the PoW camp, we asked the Chinese to take us to the graves of our soldiers who had died in our camp. There were seven of them, including Subedar Joginder Singh, who had been awarded a PVC.

The Chinese told us that he had refused to have his toes, which were affected by frostbite, amputated. According to the Chinese, he had told them that his chances of promotion to Subedar Major would be adversely affected if his toes were amputated. We were told that he died of gangrene.

On March 28, we left the camp, ironically in a captured Indian vehicle, and were driven to Tsetang to pick up Brig John Dalvi and three other lieutenant colonels and five majors.

On March 29, we were all driven in a bus to Lhasa. On April 5, we were flown in two Il-14 aircrafts to Sinning. After a long tour of China, during which we were shown China's so-called progress after the Communist revolution, we were informed on April 27 that we would be handed over to India at Kunming on 4 May.

At the handing-over ceremony, we witnessed a last surprise performance by the Chinese. Throughout our tour of China, an immaculately dressed Chinese had accompanied us. He was not dressed in cotton-padded clothes like all the others. He commanded a lot of respect from the other Chinese. We used to refer to him as the 'general'.

At the handing-over ceremony, we witnessed a last surprise performance by the Chinese. Throughout our tour of China, an immaculately dressed Chinese had accompanied us. He was not dressed in cotton-padded clothes like all the others. He commanded a lot of respect from the other Chinese. We used to refer to him as the 'general'.

He had a chap trailing behind him always, helping him with things, offering a chair, a cup of tea, etc. We used to refer to him as the 'orderly to the general'. At the handing-over ceremony, however, the person who sat down and signed on behalf of China was the 'orderly' and the one who stood behind to pass him the pen to sign was the 'general'! Such are the ways of the Chinese!

On May 5, we took off at 9.10am from Kunming and were scheduled to land at Calcutta at 1.20pm. Before reaching Calcutta, the pilot announced that there was some problem with the undercarriage, which was not opening, and that we might have to crash land. But we somehow landed safely at 2.30pm at Dum Dum with the fire tenders all lined up. It would have been such an irony of fate if we had been killed in a crash landing in India!

We were back on Indian soil after six and a half months in Mao's land.

In conclusion, I would like to say something that still hurts me 40 years later. Some authors have written that the Chinese attack came as a response to India's 'forward policy'. This is utter nonsense. The Chinese had prepared this attack for at least two or three years before.

We saw ample evidence of this on our road to the camp. How ammunition had been stocked, how they were prepared in every field. The PoWs from the Ladakh front confirmed that they too had observed the same state of meticulous preparation.

I can give you a few other examples: one day, much to our delight, a Chinese woman came and recited some of Bahadur Shah Zafar's poems to us. The Chinese had certainly prepared for this war most diligently because they had interpreters for every Indian language right in the front lines.

This Urdu-speaking woman must have lived in Lucknow for a long time. Same thing for one of our guards; though he had not said a single word for five months (we used to call him Poker Face), we discovered that he could speak perfect Punjabi when he left us in Kunming.

In Kameng FD itself, they had many local people on their payroll. They had detailed maps and knowledge of the area. How otherwise could you explain that they were able to build 30km of road between Bumla and Tawang in less than two weeks?

But their constant brainwashing was to make us accept that we had attacked them.

One day, Lt Tong took us out and we were allowed to sit against a wall to sun ourselves. Though we could not see over it, we heard voices in Hindi from the other side. It was a Hindi-speaking Chinese talking to some jawans. The talk was going in the usual way about how India had attacked first.

A jawan told the Chinese that his company was sleeping when the Chinese attack came, so how could India have started the war? The Chinese tried to explain that the jawan was only thinking of his own unit, but India had attacked elsewhere and China had to take action in self-defence.

The jawan was fearless and outspoken. He answered: "I do not know what you are talking about, but the whole of my 'burgerade' (Punjabi for 'brigade') was sleeping when you attacked first."

It is sad that this nonsense of India attacking China is still prevailing today in some quarters.

A last anecdote. One or two years after the war, I once saw Gen Kaul at the Grindlay's Bank in Delhi. By that time, he had retired. I went up to him and wished him. Kaul looked bewildered and had tears in his eyes. I was surprised, thinking I'd upset him somehow. "Do you recognize me, sir?" I said. "I was your Commander Signals."

Moved, he hugged me and said: "Of course, Krishen! I recognize you. But do you know that you are the first officer to greet me? Usually when my officers see me they turn their heads and pretend not to recognize me!"

Like Nehru, he was a broken man.

A highly decorated officer who joined the British Indian Army in early 1942, K K Tewari was taken prisoner during the Chinese attack on India on October 20, 1962, when he was visiting the forward troops. He spoke to Claude Arpi.