The Rediff Special/G Vinayak

DAY I: Guwahati -Tenga

DAY I: Guwahati -Tenga

It takes about four hours from Guwahati to reach Tezpur, the headquarters of the Indian Army's IV Corps, which looks after the Chinese Frontier in addition to counter-insurgency duties in Assam. So one had to start early in order to catch the top brass of the IV Corps.

We-Anupam, the photographer and I-start at six, having mentally prepared ourselves for a week-long sojourn to the Kameng Frontier, the scene of battle in 1962 when the Chinese came pouring into the then NEFA (North East Frontier Agency) in October-November.

As we cross the three-km long Koliobhomora bridge across the mighty Brahmaputra near Tezpur, I recall having read and heard from those who were staying at Tezpur in those turbulent times, that the very road that we were traveling now was a choc-a-bloc with people fleeing Tezpur town. There is one major difference now though: there used to be no bridge back then. Large ferries used to operate between Bhomoraguri (on the north bank of Brahmaputra) and Silghat.

We reach the heavily fortified Corps Headquarters around 10 am.

The IV Corps has come a long way from its formation during the Chinese aggression. Back then it was a hastily assembled force, born out of the short sightedness of the then politico-military leadership. It had disintegrated as quickly in the face of a vastly superior enemy, both in terms of numbers and preparedness. But in less than nine years, by 1971, the Corps had won back its prestige in the battle for East Pakistan and creation of Bangladesh.

After meeting some of the officers (no one is allowed to be named or quoted at the moment since Operation Parakram and the consequent high alert is still on) we commence the next leg of our journey. The destination: Tenga Valley-the Divisional headquarters.

As we leave the plains of Assam and climb the hill to come to Bhalukpong, the entry point into Arunachal Pradesh in this sector, the policemen at the check post take a close look at our Inner Line permit, the document that allows non-Arunachalis to enter the state on a temporary basis. The moment the driver of our Tata Sumo drops a hint to the policemen that we are journalists, we are waved on.

Then I remember that the Chinese had come right upto Bhalukpong-barely 50 km from IV Corps

headquarters at Tezpur!

Then I remember that the Chinese had come right upto Bhalukpong-barely 50 km from IV Corps

headquarters at Tezpur!

In another two hours we bring out our pullovers as the chill in the air is increases in direct proportion to the rise in altitude. At Seppa, the Military Policeman notes our details so that he can pass on the message to the next checkpoint. It is, we are told by the NCO manning the post, a precaution more than security, since the hill road is tough to negotiate.

"This system helps us to keep a track of all the vehicles traveling on this road and just in case there is break down, mount a rescue operation," he explains. Indeed the road becomes steeper and narrower as we go along. At a stretch between Seppa and Nechifu, we encounter thick fog, the driver unable to see beyond the vehicle's bonnet. The progress is painfully slow.

By 4 pm, as dusk is about to dissolve into the night we are at Tenga, a vast valley just below the district town of Bomdilla.

This is the headquarters of the "Ball of Fire" Mountain Division that is entrusted with the task of manning the Kameng Frontier facing the Chinese across the McMohan line. We are supposed to

halt for the night here since driving in the hills after dark is generally avoided. We check into the Border Roads Organisation (BRO) Guest House on the bank of small rivulet.

Dinner is served early since we have to leave for Tawang by 6 am on the morrow. As I scribble in my notebook the details of the day-long journey, my last thoughts before sleep are about the extreme cold that we are likely to encounter up there. Even the thick quilts provided by our hosts doesn't block the numbing chill that sets in with nightfall.

Day II: Tenga-Tawang via Sela and Jaswantgarh

The day is bright and sunny, raising our hopes that the cold would be tolerable as we proceed. By end of the day, we could not have been more wrong. Just out of Tenga, another army checkpost again takes down our details. For the next six days we were to encounter this practice repeatedly.

The distance from Tenga to Bomdilla is just 20 km but we ascend almost 4,000 feet in that short distance. Bomdilla is now a flourishing town but in 1962, it was an obscure little settlement. It was also a place where retreating Indian forces tried to hold the rampaging Chinese but to no avail. We try to locate someone who has witnessed the actual fighting but in Bomdilla such a person is

unavailable at that moment.

The distance from Tenga to Bomdilla is just 20 km but we ascend almost 4,000 feet in that short distance. Bomdilla is now a flourishing town but in 1962, it was an obscure little settlement. It was also a place where retreating Indian forces tried to hold the rampaging Chinese but to no avail. We try to locate someone who has witnessed the actual fighting but in Bomdilla such a person is

unavailable at that moment.

In 1962, we are told, it was rare to find an Arunachali holding a senior official position in the

administration since NEFA was under the charge of the Foreign Affairs ministry which administered the territory through the now-defunct Indian Frontier Administrative Service (IFAS). The lower echelons of the government machinery were manned mostly by the Assamese and the Bengalis.

After an hour-long, lonely journey with only an occasional civilian vehicle passing by, we arrive at Senge, a transit camp at an altitude of 9,000 feet. The camp is the starting point of an acclamatisation schedule for every soldier posted in this sector. Each armyman posted in the Kameng sector has to follow the "acclimatisation" schedule.

"Each soldier, including office

rs have to spend the first six days at Senge. During these

six days, troops are advised to rest on the first two days followed by short walks on the next two. In the final two days, jawans and officers alike are supposed to walk at least five km. The next halt is at 12,000 feet. A similar but shortened routine is followed at this height. Once this is done, soldiers are ready to be at heights above 15,000," reveals the Officer-in-charge of the transit camp.

Officers tell me that the system is strictly adhered to. In the aftermath of the 1962 debacle, the Army has clearly learnt its lessons since during that war soldiers were pushed into the

battles without acclimatization, proper winter clothing or sufficient rations. Now, there is no such shortcoming. Adequate rations, an all-weather road and proper amenities are provided

to the soldiers. Jawans and officers alike are provided with the best possible living conditions. Each post is provided with a generator and a dish antenna for television entertainment.

Officers tell me that the system is strictly adhered to. In the aftermath of the 1962 debacle, the Army has clearly learnt its lessons since during that war soldiers were pushed into the

battles without acclimatization, proper winter clothing or sufficient rations. Now, there is no such shortcoming. Adequate rations, an all-weather road and proper amenities are provided

to the soldiers. Jawans and officers alike are provided with the best possible living conditions. Each post is provided with a generator and a dish antenna for television entertainment.

After a quick lunch, we are off again. The weather is closing in on us and as we come to Sela Pass (at 13,700 feet), it is totally misty and extremely cold. Sela is the highest point in the Tezpur-Tawang Road. From here on, it is a downward journey.

An hour after Sela, we come across a unique memorial-cum-mandir of Jaswant Singh Rawat alias Jaswant Baba. The story of Jaswant Singh Rawat is inscribed in a plaque at the memorial. The

caretaker of the memorial also takes pride in recounting Jasawant Singh's heroics.

It was the final phase of the war in November 1962. Even as his company was asked to fall back, Jaswant Singh remained at his post at an altitude of 10,000 feet and held back the rampaging

Chinese for three days single-handedly. He was helped by two local girls -- Sela and Nura -- during the heroic battle that ended after the Chinese discovered the post was being defended by a solitary soldier.

So enraged were the attackers that they cut off Jaswant Singh's head and took it back to China. However, after the ceasefire, the Chinese commander, impressed by the soldier's bravery,

returned the head along with a brass bust of Jaswant Singh. The bust, created in China to honour the brave Indian soldier, is now installed at the site of the battle, a location now known as

Jaswantgarh. Jaswant Singh's saga of valour and sacrifice continues to serve as an inspiration to all army personnel posted in this sector.

Army personnel passing by this route, be it a general or a jawan, make it a point to pay their respects here. Jaswant, who was awarded a Mahavir Chakra for his bravery is not the only

soldier to be honoured thus. We find several memorials built along the way. One of them in fact is right on the border at Bumla honouring Subedar Joginder Singh who won a posthumous Param Vir Chakra for his bravery.

Army personnel passing by this route, be it a general or a jawan, make it a point to pay their respects here. Jaswant, who was awarded a Mahavir Chakra for his bravery is not the only

soldier to be honoured thus. We find several memorials built along the way. One of them in fact is right on the border at Bumla honouring Subedar Joginder Singh who won a posthumous Param Vir Chakra for his bravery.

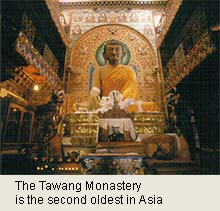

In a way, the Indian Army is trying to overcome the one big blot it has on its record by officially recognizing the 2420 dead warriors in the 1962 conflict. The Army has constructed a huge

war memorial at Tawang. The magnificent Tawang War Memorial, inaugurated by the then Eastern Army Commander Lt. Gen. H R S Kalkat in November 1999, has a 40-feet high Stupa as its

centrepiece.

A plaque at the entrance which says, 'A nation that does not honour its dead warriors will perish' indicates the Army's willingness to accept its defeat and learn lesson from it. Old timers say the war memorial is the first real attempt by the Army to honour those who died fighting a vastly superior and well-prepared enemy.

As we enter Tawang, the sun is almost behind the big mountains and its getting dark. And it is only 4 pm! The pullover is no longer enough to protect us from the biting cold. Out come the heavy

jacket, the monkey cap and gloves as we head towards our night halt. Our hosts advise us not to walk to briskly since the 10,000-feet altitude can induce breathlessness and nausea.

We take the advise seriously.

We finalise our plans for the next day over an early dinner and promise to be up and about by 5 am

to be on our way to Bumla, the last frontier.

DAY III: Tawang-Bumla and back

Given the extreme cold, a bath is out of question, so we are ready in a jiffy first thing in the morning and off to Bumla, also called heap of stones since this is the spot through which

the famous McMahon-the boundary between India and China-line runs. As we negotiate the steep climb through thick snow-the vehicle has to be a four-wheel drive and preferably the sturdy Jonga with its 3000 cc petrol engine-we come across quaintly named spots like Maratha ground, Y junction and PTSO or Madhuri lake. Each place has a history.

The Maratha ground for instance, complete with a statute of Shivaji is so named since a Maratha Light Infantry unit was the first to come and establish a proper infrastructure here. Y junction is the place where the road forks into two directions. PTSO lake was named after a lady Chinese engineer who had apparently supervised the construction of the Bumla-Tawang road with the help of Tibetan conscripts to enable the Red Army to sweep through Indian forward defences until filmmaker Rakesh Roshan decided to shoot a portion of his film Koyla starring Shah Rukh Khan and Madhuri Dixit here in the mid-Nineties. The lake was promptly renamed as Madhuri lake by the romantic jawans!

At last we arrive at Bumla (la, incidentally means a pass) where the Indian and Chinese force commanders on either side of the border meet every six months to sort out any minor problems.

Till two-three years ago, temporary tents used to be pitched for the Border Personnel Meetings but now a proper conference hall has been built to host these crucial meetings.

At last we arrive at Bumla (la, incidentally means a pass) where the Indian and Chinese force commanders on either side of the border meet every six months to sort out any minor problems.

Till two-three years ago, temporary tents used to be pitched for the Border Personnel Meetings but now a proper conference hall has been built to host these crucial meetings.

Officers posted in the sector tell us that there has been a lot of lowering of tensions on the border in the past 15 years, especially after confidence building measures were initiated in the aftermath of Rajiv Gandhi's breakthrough visit to Beijing.

Since 1987, both China and India have de-escalated their troop strength on the border. Instead of nearly three divisions at one time in the late Seventies and early Eighties, India has a

little over a brigade strength (over 5,000 troops) in this sector now. China has also correspondingly reduced its strength.

But reduction in troop strength however does not mean that India is complacent. As a senior officer puts it: "Our defences are impeccable now. I think the other side knows this. Still we don't take any chances."

Caution is a constant watchword here. Officers posted in the sector repeatedly emphasise that Beijing can never be trusted.: "One should not forget that the Chinese waited for 24 years before attempting another mischief at Sumdaroong Chu. What is the guarantee that they will not do it again? After all, Beijing still maintains that Arunachal Pradesh is its territory," said a senior officer.

It is in this deceptive calm that the Indian soldiers do their job.

Since newcomers and un-acclamatised, unfit civilians like us are not meant to stay at such heights (over 16,000 feet), we make a quick getaway after the mandatory hot pakoras at the outpost and

have a leisurely lunch at the battalion headquarter before heading back to Tawang for a well-deserved rest.

Analysts and political pundits will have their own take on the relative strengths and weaknesses of the two sides, but the nearly two-and-a-half day journey from Tezpur to Bumla is enough

to convince me that come what may, there would be no repeat of 1962 in an eventuality of another war in this sector. The Indian Army, 40 years after its most shameful moment, emerged stronger

and more professional. The preparedness is first rate, the morale higher and the capability enhanced.

Photographs: A Nath