His dark brown eyes stare at the plastic ball his friend lofts over the fence of their dusty neighbourhood park. He watches with envy as another boy runs after it. A game of cricket is in progress. The players are children aged 14 to 16. There are no eligibility criteria but still he cannot play.

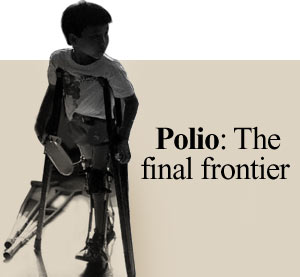

For Samie Siddique, 14, suffers from polio. He lost the movement of his legs in early childhood. Crutches are his constant companions.

Samie is one of 20 million Indians crippled by polio over the years.

Passionate about cricket, Samie dreams of hitting sixes and fours in crowded stadiums. "Papa says I will be alright. Then I will play like Tendulkar and hit the ball out of the ground," he says hopefully.

But some dreams are destined to remain dreams. Samie will never be cured.

"Once the polio virus infects a person and paralyses him, it destroys the motor nerves which control movement. The infected limb is gone for over," says Dr Jay Wenger who heads the World Health Organisation's National Polio Surveillance Project in India.

Medical specialists have been fighting to eradicate the virus for decades. Thanks to massive immunisation campaigns, the war against polio has reached its final stages. "The endgame has begun," says Dr Wenger.

Earlier this month, India launched its largest ever immunisation campaign to root out polio. A million volunteers fanned villages, towns and cities to vaccinate India's 165 million children under the age of five.

The immunisation drive was preceded by a high profile publicity campaign. Amitabh Bachchan appeared in television commercials, asking parents to immunise their kids. The polio drive was deliberately timed to begin with the cricket World Cup. It helped the campaign reach larger audiences as cricket lovers were glued to television sets throughout the country.

"UNICEF and the government decided to come out with a very strong media campaign. We approached Mr Bachchan and he did the campaign for free, as a service to the nation," says Michael Galvea of the UNICEF communication unit.

In the worst affected Uttar Pradesh, door-to-door campaigns were part of the mobilisation drive. Uttar Pradesh accounted for most of the 1,323 polio cases in India last year, which comprised 85 per cent of global polio figures. Around 10 per cent of the state's 33 million children -- 250,000 babies are born in the state each month -- have not been vaccinated against the disease. The entire focus of the immunisation campaign is Uttar Pradesh. Last year, polio cases were reported from 64 out of its 70 districts. It was an epidemic, said Galvea.

High population growth, overcrowding, poor sanitation and ignorance contribute to the high incidence of polio in the state. WHO experts concluded that the rise in polio cases was also because of the chronic failure to improve immunisation coverage in western UP. Besides, some Muslims stayed away from polio campaigns in the state. Immunisation was rumoured by miscreants to cause impotence and aimed at stunting the community's numerical growth.

In 2001, the World Health Organisation's global campaign to eradicate polio had reduced the number of cases worldwide to 483. WHO then set a 2005 deadline to eradicate polio. But the disease resurfaced in India last year, reducing WHO's chances to meet the 2005 deadline. Around 1,300 cases were reported in 2002, according to WHO, while only 258 cases were reported in 2001.

The rise was disappointing, as the number of cases reported from India had come down drastically after 1999. Compared to the 1,126 cases in 1999, barely 265 cases were reported in 2000, as per statistics available with WHO, which has been running the National Polio Surveillance Project in association with the government of India since 1997. Not only had the numbers fallen, but polio had been limited to Uttar Pradesh and Bihar after 1998.

Medical experts have a theory to explain the increase. Based on statistics of the polio cases reported over the years, they believe there is a cyclical increase in such cases every year. "2002 was the fifth year in that curve. That is a reason for the increase in the number of polio cases," says Dr Wenger.

When the global campaign to eradicate polio was launched in 1988, the disease was endemic in 125 countries and affected 350,000 people every year. In 2002 it affected 1,866 people and was endemic in only seven countries -- Nigeria, Niger, Egypt, Somalia, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. Europe had been declared a polio-free zone some years ago. As were the United States, the Americas, China and far-east Asian countries like Japan.

Spearheaded by WHO, the global campaign costing millions of dollars was expected to eradicate the disease by 2000. That did not happen, so the deadline was extended till 2005.

Will WHO meet its deadline this time? It seems to be a tough job, as new cases have been found not only in India but also in Afghanistan, Pakistan and some African countries. For a country to earn the polio-free laurel, no new case should have been reported for about three years. That leaves India and the other polio affected countries with 2003 as a deadline.

Many believe India will not be able to declare itself a polio-free country by 2005. "It is a difficult task, but we might meet the deadline. A similar increase had occurred in Congo before it eradicated polio. It also helps in identifying the susceptible areas and you go for another vigorous campaign there," says Dr Wenger.

Which is exactly what WHO is planning for western and central Uttar Pradesh, which reported more than 90 per cent of India's cases this year. It is going for more rounds of intensive immunisation campaigns in April, June, September and January next year, which experts hope will stop further transmission of the virus.

Polio usually strikes children under the age of five. It can cripple the spinal cord and brain, causing paralysis and even death. It is transmitted through food or water contaminated by the faecal matter of an infected person. Like small pox -- which caused the death of thousands of people -- it needs a human agent for its survival.

Smallpox was declared eradicated in the 1970s; no case has been reported since. It gives hope to those working against polio.

"Polio will be eradicated for good," Dr Wenger says. The discovery of new cases, experts say, shows the effectiveness of the Polio Surveillance Project, which involves thousands of campaigners at district and block levels.

But polio cannot be battled only on the medical front. It includes psychological support for the victim from his/her family and from a society where many look down upon patients like young Samie.

"We had to pull him out of school for some time," says Samie's father, "as some kids would make fun of him. Later, I spoke to the teachers and encouraged him to join the school again. Now he has learnt to cope, but there are times when he is depressed by his condition."

Design: Dominic Xavier