In the early 1960s, journalist and Sikh historian Khushwant Singh met with a group of hippies who told him that they  had left America for an Indian sojourn because they were fed up with materialism. Singh told them Indians were fed up with ubiquitous poverty, and would gladly welcome some materialism for a change.

had left America for an Indian sojourn because they were fed up with materialism. Singh told them Indians were fed up with ubiquitous poverty, and would gladly welcome some materialism for a change.

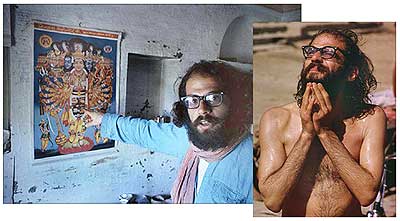

One wonders how Allen Ginsberg, the radical poet who mocked American materialism in his celebrated poem Howl, would have taken Singh's response. Ginsberg, 35, had left New York in 1961 by boat for Bombay, along with troubled lover Peter Orlovsky, and persuaded poets Gary Snyder and Joanne Kyger, then living in Japan, to join him.

In her luminous book A Blue Hand: The Beats in India, Deborah Baker talks of how Ginsberg's trip played out against the backdrop of the criticism, praise and relentless notoriety that followed the publication of Howl.

|

In India, Ginsberg lived in flea-pit hotels, did drugs, spent hours at the burning ghats trying to overcome his fear of death, sought out godmen and their prescriptions for nirvana, spent time with the rebellious young poets of Kolkata a multihued experience Baker captures immaculately in her book.

Baker writes of the mysterious Ashoke Sarkar, who would later take Fakir as his last name, and who took Ginsberg to the ghats outside Calcutta so he could witness 'the exact process by which flesh was transformed into bone and ash.' Ginsberg preceded the trip with a hearty meal in Kolkata's Chinatown and, on arriving at the crematorium, smoked ganja (marijuana) and settled down to 'watch the stream of corpses arrive on charpoys bedecked with flowers, the pyres roaring around them.'

Baker, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, has visited Kolkata almost every year since her 1990 marriage to distinguished novelist Amitav Ghosh, and all the colour and light absorbed during her many trips illuminates her book, packed with colorful anecdotes that underline the central point: That Ginsberg's Indian journey played an important role in the counter culture movement of the 1960s and the next decade. The poet returned to America after his India sojourn even more fiercely anti-war than before.

It is an unblinkered look at a person who stood for the time Baker, thus, does not shy away from showing up the contradictions, and limits of idealism, in Ginsberg and his lover. She also sets Ginsberg's mysticism in context, taking us to the summer of 1948 when Ginsberg, a Columbia University undergraduate subletting an East Harlem apartment, heard 'an unearthly voice' reciting the William Blake poem he had been reading. This was followed by a vision of 'a living hand [that] had placed the whole universe in front of me. ... the sky was the living blue hand itself.'

Irwin Allen Ginsberg suddenly became, writes Baker, 'a divining rod in the headlong and holy pursuit of God.' The Indian journey, which took nearly one year, is intimately connected to that earlier mystical experience.

Baker also shines light on the inner hell that would possess Ginsberg from time to time, especially during the decade preceding his Indian visit. Among the many traumatic experiences he suffered was his mother's institutionalisation and gloomy death.

A Blue Hand has received excellent reviews in the mainstream media, and some of the best writers in America and Canada have welcomed the book with thought-provoking blurbs. "Baker captures the range of their [Beat poets including Ginsberg and his friends] artistic and spiritual passions, as well as their pettiness, their tantrums, their always difficult loves," says Kiran Desai, author of the international bestseller The Inheritance of Loss.

Michael Ondaatje called A Blue Hand "a fabulous book - comic, tragic, and written with great verve and nerve - about the Beats and their passage to India. It is a remarkable saga of various lives and stories all drawn together by Deborah Baker - the biographer as adventurer."

Baker says she wanted to tell a story larger than the experience of the Beats in India. "Part of what I wanted to explore in my book was how India appeared in the American imagination from Walt Whitman to Allen Ginsberg and from Christopher Columbus to Jackie Kennedy," she says. "When Ginsberg contemplated the idea of India before he actually arrived there, he was afraid of falling ill to some dread disease, of being terrified by the extremes of poverty."

Ginsberg, however, was equally of the opinion that he could never, in America, succeed in his quest to know more about God, and to have a mystical connection with God. "In India, he felt he would have to pass through this terror to come to know God in a way that was impossible for him to in America, where the sense of the sacred had all but disappeared, subsumed by postwar capitalism, materialism, parochialism, and rigid conformity," Baker said.

Ginsberg had read a lot of Indian religious literature, but was never sure what he was going to encounter when he landed there. "It wasn't until he arrived and immersed himself in his Indian journey that he realised that India is an actual place, with a specific history and geography, with a huge range of languages, religious traditions, ethnicities," Baker says. "I think he exulted in the multitudinous realities of India, the many different ways of knowing God and celebrating the divine and the human in everyone."

Kolkata in particular called to the poet. "He loved Calcutta best, because it was a city that honoured poetry and where poets were worshipped like minor gods," Baker points out. "It was also where he made his most lasting friendships with the great Bengali poets Shakti Chatterjee and Sunil Gangopadhyay."

Calcutta also tested Ginsberg's idealism, especially when he helped the penniless, and the leprosy patients. As Baker says in the book, Ginsberg after helping several lepers and beggars, particularly a mute, for many weeks, 'began to resent the thought that whether any of them lived or died depended on the pittance he provided.'

Baker writes of how a sadhu watched Ginsberg bathing the mute and told him he was committing a sin. That led Ginsberg to think about the 'use of helping the man get better when he would only have to go through the horror again after he [Ginsberg] left'. Despite such doubts, and even after moving away from Kolkata, Ginsberg continued to help those desperately in need of money.

Baker also looks at some of the other people Ginsberg encountered in India, offering us intriguing glimpses into their lives, especially that of Ashoke Sarkar who would become guru to Timothy Leary, the Harvard professor who became famous for his experiments with LSD. Another colorful character is Hope Savage, a young woman whose path crossed that of Ginsberg several times, and who the poet futilely searched for later.

Though A Blue Hand is in a way about Ginsberg, Baker deftly makes the other characters including Hope Savage come alive, taking us inside their fractured lives and that is just one of the major achievements of an endlessly fascinating book.

Image: (Left) Allen Ginsberg in his Benares room and taking a holy dip in the Ganges.