Will Queen Elizabeth say sorry for Jallianwala Bagh?

Seventy eight years ago, a glorified dump was converted, thanks to the ruthlessness of General Reginald Dyer, into the spark plug that jump-started the struggle for India's Independence.

Seventy eight years ago, a glorified dump was converted, thanks to the ruthlessness of General Reginald Dyer, into the spark plug that jump-started the struggle for India's Independence.

Seventy eight years later, the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh has been converted, thanks to the desire of a handful of politicians both in India and in England, into a bone of emotive contention that threatens to shroud Queen Elizabeth's planned visit to this country in needless controversy.

The British polity and administration have, over the past 48 hours, become polarised on the question of whether or not the queen should apologise to the Indians for the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh.

The British Foreign Office, which for such matters would qualify as the official voice of government, says there is no question of the queen apologising for Jallianwala Bagh or, in fact, for any incident whatsoever connected with the British rule in India.

The India-born British MP Keith Vaz, now a junior member of the ruling Labour government, for his part has made out a strong case for an apology. "The queen should be bound by what the Indian government says, and if they think it is a bad idea for her to visit Amritsar, then she should take their advice," Vaz, who chairs the Indo-British Parliamentary Group, said in London.

Interestingly, while the question -- to apologise or not -- seems to be the crux of the controversy, all public statements, in either country, have as their starting point the statement by Prime Minister Inder Kumar Gujral which, far from asking for a mea maxima culpa, appears to go out of its way to make it unnecessary for the queen to take a public stand on the issue.

For what Gujral suggested in an interview to The Observer published on Sunday is that the queen stay away from Amritsar during her upcoming state visit, thus making defusing emotional demands for an apology and defusing what could be a potentially embarassing situation for the British Crown.

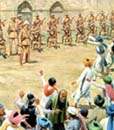

The 'strong case for apology' that Vaz refers to stems, perhaps, from the fact that General Dyer has never been punished for the atrocity, wherein on April 13, 1919, he ordered his platoon of infantry to fire into the citizens assembled at Jallianwala Bagh as part of the Baisakhi celebrations.

Official accounts put the toll at 379 killed and around 2,000 wounded. Dyer, for his part, received a purse of 20,000 pounds (raised unofficially by the British public). In fact, through the rest of his life, Dyer maintained that the carnage had been a "jolly good thing" -- a sort of 'put them in their place didn't I?' attitude that, officially, Britain did nothing to censure.

The "jolly good thing", however, had the unintended effect of undercutting Britain's claims to the high moral ground in its continued hold on its Indian empire.

In a debate in the British parliament in May 1919, a Conservative MP said, "If we do not hold India by moral suasion, we must hold it by force -- possibly thinly veiled, but undoubtedly by force."

A diametrically opposite view was, however, held by Indians. Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore, while relinquishing his knighthood in protest against the carnage, said, "Considering that such treatment has been meted out to a population disarmed and resourceless by a power that has the most terribly efficient organisation for the destruction of human lives, we must strongly assert that it (Britain) can claim no political expediency, far less moral justification."

In the event, the outrage at the massacre welded the Indian public into a cohesive whole behind the leaders of the freedom struggle. And in that sense, Jallianwala Bagh could well be, in the hindsight of history, the point that marked the beginning of the end of British rule in the Indian sub-continent.

Ironically, the question of 'apology' could play as important a part in Indo-British relations in the future, as the original incident played in the past. Last week,

India's high commissioner to Britain Dr Laxmi Mal Singhvi told the media that "They

(the British) ought to make their common cause with us

(Indias) rather than with their ancestors in the atrocities.''

And analysts indicate that the question of Jallianwala Bagh could well impact on economic relations between the two countries in the future -- the unstated sub-text of Vaz's 'case for apology'.

It is not as if apologies for historic wrong-doings and

atrocities are unheard of in Britain. The Labour government of

Tony Blair recently apologised to Ireland for Britain's role in

exacerbating the Irish potato famine. The apology came on the 150th anniversary of

the famine.

It is not as if apologies for historic wrong-doings and

atrocities are unheard of in Britain. The Labour government of

Tony Blair recently apologised to Ireland for Britain's role in

exacerbating the Irish potato famine. The apology came on the 150th anniversary of

the famine.

In one of his first acts after forming a government, Blair apologised for the British

policies which, he admitted, had escalated the spread of potato blight

in Ireland from a famine into a massive human tragedy.

The queen, too has said 'sorry' for the country's historic sins. On her

last visit to New Zealand, she apologised to the indigenous Maori

people for the expropriation of their land by the British in the

19th century.

All of which leads up to the question exercising two nations today -- will the Queen, on her forthcoming visit, attempt by means of a graceful apology to, if not obliterate the tragedy of Jallianwala Bagh from the collective Indian memory, at the least paper over the bullet-pocked walls that remain in mute testimony to one of Indian history's most horrific moments?

|