He made the songs Aap Jaisa Koi and Disco Deewane a rage in the 1980s. In fact, Feroz Khan's Qurbani -- which featured the first song -- became a huge hit, thanks mostly to its foot-tapping music.

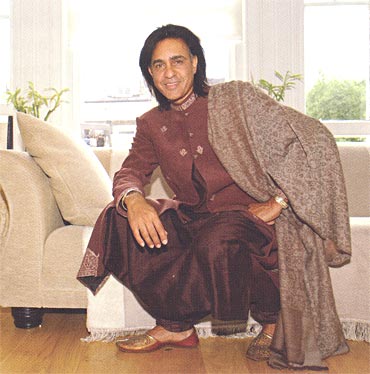

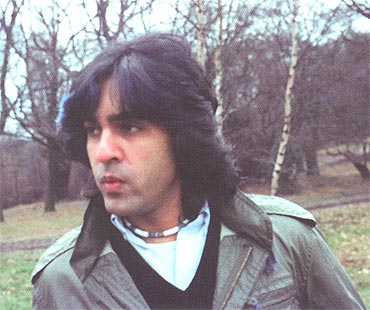

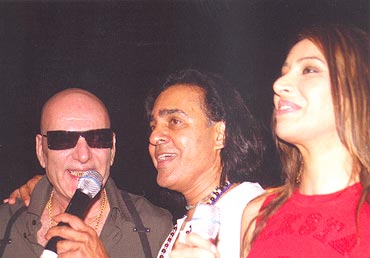

And the man behind the music was Biddu, whose musical talent is not much seen these days.

Biddu penned his autobiography, Made in India Biddu: Adventures of a Lifetime, and recounted his life's highs and lows very well. We present an excerpt from the book, where Biddu talks about his musical peak in 1980:

I got back into the routine of my life -- one eye on my music and the other on helping my wife bring up our two kids. Perhaps it was tradition and my cultural inheritance speaking to me through the deepest stratum of my subconscious, but I wanted to be a hands-on father. I was beginning to see the break-up and desecration of the family unit in the West and, more pertinently, in the UK.

Vast numbers of old people lived in isolation, detached from the umbilical chord of their children's touch and concern. It was a time of Thatcher's Britain and though she took us out of the economic quicksand we had sunk into, and felled the power of the unions like a dragon-slayer, she had also taught us to worship at the temple of materialism and that greed was god and no price was too high to pay for it. We were turning into an 'I, me, my' society. I was a part of that society and yet I wanted to be apart from it. Easier said than done, I'm afraid.

Then, one morning, I got a call from Feroz. He sounded decidedly upbeat.

'Bidz, the song is killing them, man,' he said with typical filmi hyperbole. 'They are going crazy for it.'

'What are you talking about, Feroz?' I asked, unhinged from the chore of changing little ZaZa's nappies.

Excerpted from Made in India Biddu: Adventures of a Lifetime, by Biddu, HarperCollins India, with the publisher's permission, Rs 399.

'The song, man! Aap Jaisa Koi. The song you did. People are going crazy about it,' he said.

'I see,' I said phlegmatically.

Neither my indifference nor the crackling telephone line would dampen his enthusiasm. It slowly began to dawn on me that the song I had composed for his film was making tsunami-size waves.

'I am happy for you, Feroz,' I finally said, cheerfully.

'The film opens tomorrow in Bombay and next week in Bangalore.'

'I can't, Feroz.'

'Man, I'm sending you a ticket, you got to come. You're a Bangalore boy,' he said, not willing to settle for a no.

So the following week, I flew to Bombay and caught a connecting flight to Bangalore, reaching there at 5 pm. I stayed with my mother, who was as pleased as punch and attended the premiere that night. The next morning, I did the journey in reverse, returning to London. The whole tamasha took forty-eight hours.

Qurbani was a massive hit. It wouldn't be wrong to say that while the film was pretty good, it was the music and two songs in particular, Laila O Laila and Aap Jaisa Koi which lifted it to super-hit success, if I may indulge in some filmi hyperbole myself. Aap Jaisa Koi went on to become one of the most successful film songs of all time. It was choreographed on a delectable young actress called Zeenat Aman. Feroz was holding three aces. The man's gamble had paid off and he deserved it. He had put his money where his mouth was. I always think of him as the last of the Mughals.

Ironically, despite the immense success of my song in the film, there was no stampede to my door in London W8. In fact not a single film producer came knocking. It wasn't as if I was hiding in some isolated Hebridean island, my number was in the phone book. But perhaps Indian producers at the time were illiterate and could not read, and certainly judging from some of the scripts and storylines there is some credence to this theory. Anyway, almost a year passed by without so much as a tinkle when my doorbell did ring one afternoon and standing outside was a young man from the London branch of an Indian record company.

His name was Vinod Kumar and he represented the largest Indian music company, called HMV (later to be known as SaReGaMa). He introduced himself to me, and after my initial surprise, I invited him in.

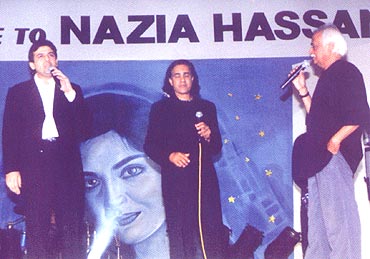

'We would like you, sir, to make an album with Nazia Hassan, the singer,' he said respectfully. The way he put it, I assumed there was also a Nazia Hassan who was not a singer.

I probed him with a hundred questions about the Indian record company.

'Our head-office is in Dum Dum,' he said, enthusiastically.

'Where, where?' I asked, jokingly.

'Dum Dum in Calcutta,' he clarified. 'We have the largest repertoire of film music in India, dating back to the forties.'

'How many non-film albums has your company released?' I asked.

'None,' he replied, looking at me as if I was dumb. 'All music in India is from films.'

I suddenly remembered that this was true. Apart from a few religious albums -- of bhajans -- which sold about a hundred copies each, it was only film songs that dominated the market. On average, a Hindi film had between seven to eight songs. It will probably be easier to locate Osama Bin Laden than find a Hindi film without songs that allowed to the actor to run around a tree wooing his love, or a female lead coming out of the waters of a gentle stream, her wet and dripping sari clinging to her buxom figure.

'So you want me to do a non-film album with Nazia?' I looked at him, incredulously.

He nodded, which I took to mean yes.

'How many copies do you think you can sell?' I said, worriedly.

'We hope with both your names we can achieve sales of forty to fifty thousand,' he replied optimistically.

In his opinion, this would amount to the album being a major success. With no film or television to back this product, the figure of 50,000 that he quoted would indeed be phenomenal.

'What about royalties?' I asked. It was my favourite word after discount.

'We don't pay royalties. Only a token lump sum for producing the album,' he replied.

'I don't work without royalties,' I replied firmly.

There was an uneasy silence in the room.

'Can I speak to my boss, Mr Sood, in Calcutta, and get back to you in a day or two?' he said apologetically.

'Don't bother if there are no royalties involved,' I said, sounding marginally annoyed.

No one in the West worked in the music industry without royalties. The Beatles were earning around 5 million a year from various royalty streams from songs and record they made in the 1960s and '70s. Royalties were a musician's insurance against penury in old age.

Young Mr Kumar called back the next day. 'Yes, royalties will be payable to you. This is an unusual case, because we don't normally pay royalties.'

'Your company should get used to it,' I replied. 'That's how it works in the West. It's only fair.'

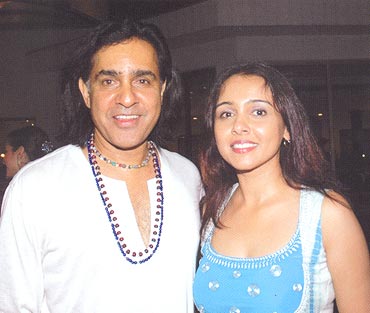

We met once more, this time with Nazia and her brother Zoheb. I was not keen on composing all the songs for the album as it would be too much of a workload trying to be creative in a style I was not familiar with, so it was decided that Zoheb would work a few tunes as well. I set about composing the melodies and in a couple of weeks, I had a batch of songs I felt extremely happy with.

I must say I also derived a certain amount of joy and satisfaction in composing those tunes. I was doing something new, almost novel; so a certain amount of passion went into the composing. Zoheb for his part also came up with three songs of merit. Bearing in mind he was only sixteen years old, I was highly impressed.